It is ironic and sad that balloons, meant to convey a message of compassion, love, and best wishes, become anything but when they are lost and become marine debris. Balloons may be ingested by marine animals, their ribbons can entangle marine life, and when they are deposited on the beach, sometimes hundreds or even thousands of miles from where they were first lost, they add to the marine debris burden on the beach ecology. Rubber balloons disintegrate slowly over time, but balloons made of plastic film, as well as plastic ribbons tied to the balloons, remain in the environment for many years.

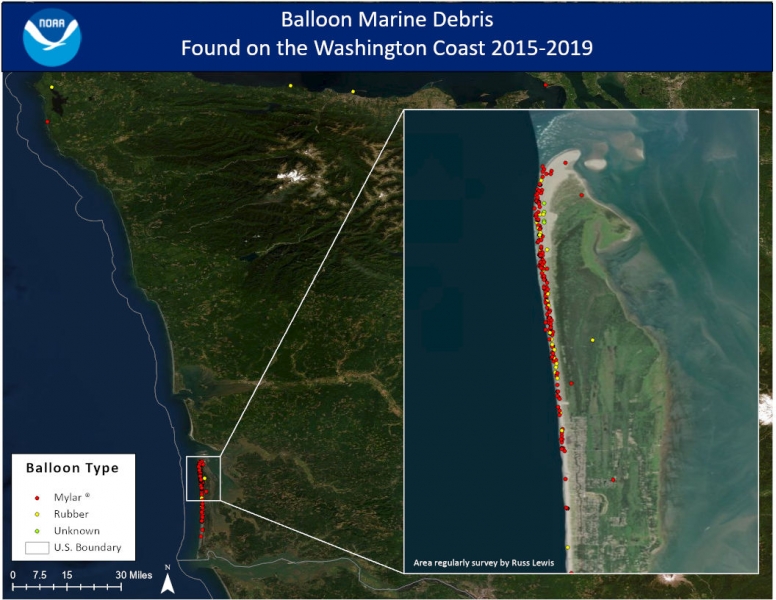

How big is the balloon problem on the Washington Coast, and what is the composition of the balloons found? Five years ago, partners working on the coast provided anecdotal data by reporting balloons they found during their survey work or beach cleanups, and the results were posted in a blog. Thankfully, Russ Lewis, a dedicated volunteer who cleans up the northernmost seven mile stretch of the Long Beach Peninsula, volunteered to continue with the balloon collection and reporting after the blog was posted. He meticulously records the location of and photographs each balloon he finds. Thanks to his efforts and reports from other volunteers, we now have anecdotal data from February 2015 to December 2019, nearly five years.

So, what have we found so far?

First, we need to qualify that this data is anecdotal, and not an official research project. And yet, the findings give us an idea of the quantity of the balloons arriving on this section of beach and their composition. A total of 254 balloons were reported, of which 201 were made of plastic film (sometimes referred to as Mylar®) and 48 were made of rubber (five balloons had no composition data). A total of 106 balloons were found with string attached, of which 38 were made of rubber. From this anecdotal data, about four times as many plastic film balloons were found as opposed to rubber balloons, but 79% of the rubber balloons had string attached, while only 34% of the plastic film balloons had string attached.

The balloon problem is persistent. While more balloons arrived from late fall to early summer, when more marine debris washes up on the beach, Russ found them year-round. Most of the balloons seemed relatively new, probably originating from along the North American West Coast, but a few were worn out and even had some marine growth on them. They also could possibly have come from far away.

Balloons debris, and all other marine debris, is human-made and wholly preventable. To prevent balloons from becoming marine debris, we should not release them intentionally, instead choose ecologically friendly alternatives to express our love and best wishes, such as cloth banners, flags, streamers, bubbles, or origami figures. Doing so would also express our appreciation and care for the environment and marine animals.

Thanks go to Russ Lewis for his tenacity and dedication to reporting balloon findings over five years, and to Dana Wu, Heidi Peterson, and Nancy Treneman who also reported the balloons they found.