By: Nir Barnea, Pacific Northwest Regional Coordinator, and Emma Tonge, Intern, with the NOAA Marine Debris Program

Many thanks go out to Russ Lewis, Heidi Pedersen, and Dana Wu for the balloon reports.

I was on a phone interview with Glenn Farley, a reporter with King 5 TV in Seattle who was preparing a report on balloons that become marine debris, when he asked, “So, how many balloons have been found along the Washington coast?” Unfortunately, I didn’t have an answer for him. “I find balloons occasionally during marine debris cleanups, and I know that others do too, but I don’t have a number for you,” I told him. Obviously, this was one of those situations where “I’ll get back to you later” was in order.

His question made me curious, and I wanted to have a better idea of the scale of this problem. How many balloons? What type? How do we get this information? It was clear that a full scale, scientific study on the number of balloons arriving on the Washington coast would take much time and effort. But, could we possibly get current anecdotal information to give us an idea of how many balloons are found?

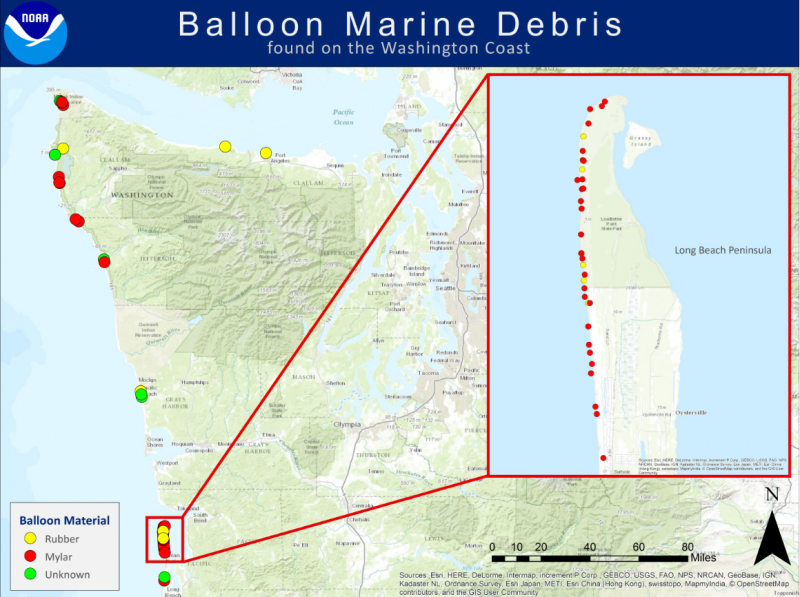

We turned to our partners who clean up or survey for marine debris along the Washington coast, and they graciously agreed to help. Heidi Pedersen, with the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, worked regularly with volunteers to conduct shoreline surveys and reported balloons found during their May 2012 to February 2015 monthly surveys of several sites. Dana Wu, with the Student Conservation Association, coordinated cleanups at remote beaches along the Olympic National Park and provided a couple of reports. Russ Lewis, a retired scientist with the National Forest Service and a dedicated volunteer who cleans up marine debris on a nearly daily basis along the north part of the Long Beach Peninsula, provided detailed reports, photos, and observations of the balloons he found.

A year has passed since we first asked for balloon reports and we now have some information and a few observations to share (keeping in mind the big caveat that this was not a scientific study).

A total of 69 balloons were reported to us. Obviously, the cleanups and surveys were done over a tiny fraction of the entire coast, and the number of balloons over the whole coast is likely many times that number. Of the 40 balloons Russ reported, 31 were made of Mylar. This is discouraging, as despite their one-time use, Mylar balloons take a long time to degrade. These balloons were more likely than other balloon types to be found individually and still partially inflated. Rubber balloons, another prevalent balloon type, were more likely to be found deflated or shredded, and often tied together in groups. Many of the reported balloons also had a plastic string attached, creating yet another hazard for marine life.

Where did these balloons come from? They most likely came by sea from other areas. The north end of the Long Beach Peninsula, where Russ did his cleanups, is not frequented by many visitors. The same can be said of most of the other areas from which balloons were reported. These balloons were thus likely lost elsewhere, ended up in the ocean, and were carried by currents and winds to the beaches where they were found.

Compared to other types of marine debris, such as single-use food packaging (think water bottles, plastic bags, plastic containers), balloons are not as ubiquitous along the Washington coast. However, they are definitely there, and like other types of marine debris, their presence is entirely preventable. Although balloons with messages such as “Congrats,” “Get Well Soon,” “Happy Birthday,” and “I Love You” are cheerful for people, they are bad news for wildlife when they become marine debris.