This week marks “Research Week” on our blog and we will be highlighting marine debris research projects throughout the week! Research is an important part of addressing marine debris, as we can only effectively address it by understanding the problem the best we can.

By: George H. Leonard, PhD, Guest Blogger and Chief Scientist for the Ocean Conservancy

Have you ever wondered how much trash is on U.S. beaches? So have we! At Ocean Conservancy, we have spearheaded the International Coastal Cleanup (ICC) for over 30 years and have collected data on the materials that are cleaned up each year. However, we haven’t done a rigorous, quantitative analysis of those data to provide a baseline by which to understand changes over time and spatial differences in marine debris across the U.S. The NOAA Marine Debris Program (MDP) has similarly monitored marine debris at a number of sites around the country, but also has not yet tried to rigorously evaluate what all the data mean. So, we have both teamed up with scientists Drs. Chris Wilcox and Denise Hardesty at Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia to bring the power of statistics to the problem. The answers are now just pouring in, and while we can’t reveal the specific findings until they are published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, we can give you a sense of what is emerging from this effort.

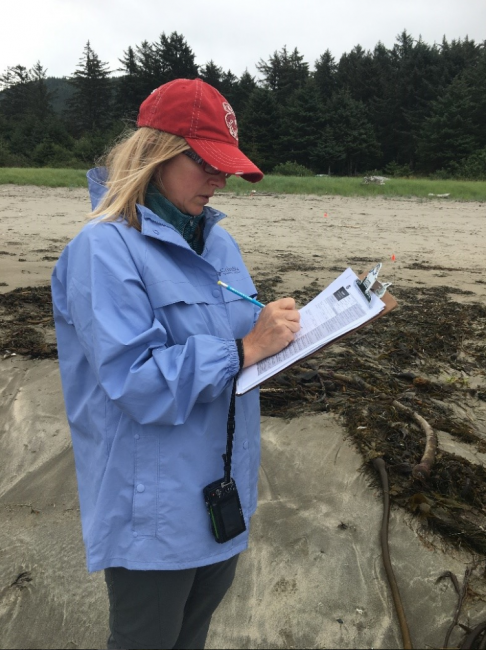

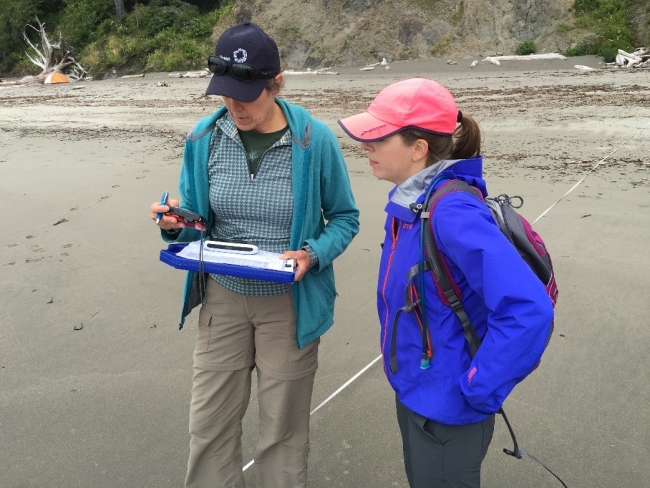

Our joint project centered on 3 core questions: 1) How much marine debris occurs along U.S. shores?; 2) Are there specific items that are most (and least) abundant, and do they vary locally or regionally?; and 3) Are there “hotspots” where marine debris is most abundant? Our approach was to bring together the ICC and NOAA datasets and statistically explore the impact of state, region, proximity to cities, presence of rivers, and observer bias on the amount and type of debris collected. We were also interested in determining if patterns in some types of debris (like bottles and caps) were influenced by the presence of local policies, like container deposit legislation.

The analysis suggests that marine debris is highly variable around the United States, with some states quite 'clean' and others quite 'dirty', on a relative scale. While these patterns are highly variable, they are also heavily impacted by the presence of people, the location of routes to the sea (like rivers), and the presence of international borders. We are also discovering evidence that local policies, like container deposit laws, can reduce the presence of commonly-littered items (such as beverage containers) on local beaches.

The three monitoring protocols that were used in this study vary in the size of debris that is recorded. The Ocean Conservancy’s ICC methods have no detection limit (so include very small and large debris pieces), while NOAA’s monitoring efforts record items down to 2.5cm (one inch) in size. Thus, these two survey types are particularly adept at identifying larger items of littered trash. CSIRO’s approach to sampling debris quantifies all debris items that are visible to the naked eye (down to about 1mm in size), which can include many of the small plastic pieces that result from the disintegration of large debris due to exposure to the elements. Thus, when evaluated statistically, estimates of the number of plastic items on the beach can vary widely depending upon the survey method used. Of course, none of the sampling methods we evaluated are capable of sampling plastic pieces that are even too small to be seen by the naked eye. If you include these teeny plastic pieces - visible only under a microscope - estimates of how much debris litters our nation’s beaches and waterways grow larger still.

One take-home message from our study? The more scientists research the issue of debris in the ocean, the more we uncover the extent of the issue and the bigger the problem seems to become. Collaborative partnerships among NGOs, scientists, and government leaders like NOAA can help quantify the scale and scope of the problem – and in so doing, lay the foundation for the solutions needed to keep debris from entering the ocean in the first place.

For more on this project check out the project profile on the NOAA Marine Debris Program website.