By Laura Ludwig, Center for Coastal Studies Marine Debris & Plastics Program

With the support of a NOAA Marine Debris Program Removal Grant, our team at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS), located in Provincetown, Massachusetts, is mobilizing fishermen and volunteers to identify, document, and properly dispose of derelict fishing gear (DFG) from Cape Cod Bay and the Cape Cod National Seashore.

The greatest amount of fishing gear in Cape Cod Bay and the outer shore is found August through October, when an average of 25,000 traps are set by approximately 75 commercial permit holders. Storm action, propellers, interaction with mobile fishing gear, and deteriorating ground lines can all cause traps to be lost. These lost traps may cause navigation hazards, damage the environment, or continue to fish for both target and non-target species.

At CCS, we recognized a need for a community approach to clearing the ocean and shore of DFG. Throughout April, when the Bay remains closed to fishing in protection of North Atlantic right whales, we take advantage of assistance from lobstermen to grapple back the DFG.

“No fisherman worth his salt would choose to lose his gear.” I coined this phrase in 2009, reflecting a zero-blame approach to engaging fishermen in DFG removal projects, and I stand by it still. Here in New England, we have worked with dozens of fishermen throughout a decade of DFG recovery efforts. We have removed thousands of pounds of debris and returned hundreds of usable traps back to their owners. We could not clean the ocean without the help of fishermen.

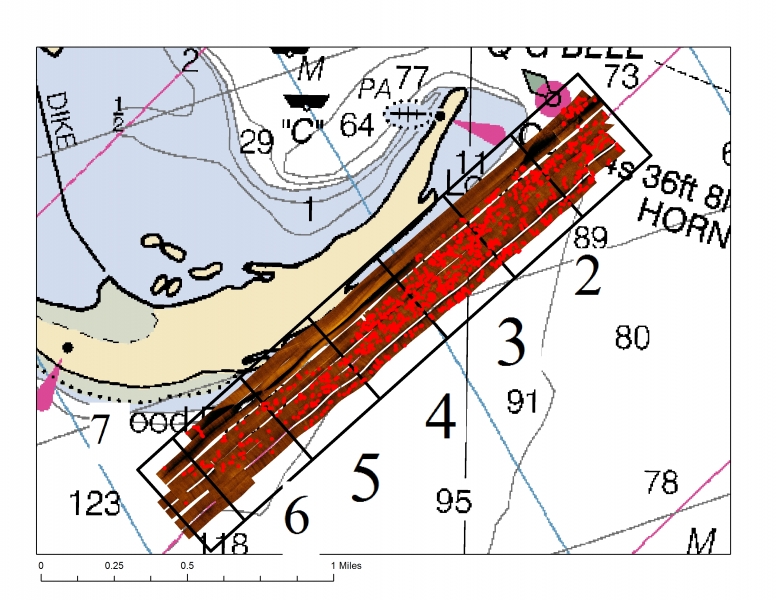

For our MDP-funded project, eight fishermen joined us for 18 days on the water. We collected over 11 US tons of gear, more than half of which was sent to a recycler.

The commercial fishermen I work with on these cleanups are stand-up characters worth every measure of their salt. They care about the health of the ocean and understand the possible impacts of lost fishing gear. They follow the rules and constantly work on their gear – repairing traps, retiring old line, tending nets – to protect their investment and ensure the viability of their harvesting operation. Rope, traps, buoys, and nets are not cheap; and today’s frayed twine or chafed groundline is tomorrow’s lost gear.

So with gear so valuable and fishermen so careful, why is there so much lost, abandoned, or derelict fishing gear on the bottom of the ocean?

Regulations exist in Maine and Massachusetts which prevent anyone from handling gear belonging to another fisherman without express permission. This prohibits a mobile fishery vessel, like a dragger, from carrying fixed gear, like lobster traps, on deck. If a scalloper accidentally drags up a lobster trap, even if the trap is mangled, the scallop boat technically cannot have the lobster trap on board, so back over it goes for us to recover in a later cleanup. Much of the gear we’ve recovered in our Cape Cod Bay project falls into the fishery-interaction category, DFG created by mobile gear fishermen following the rules.

According to the data we collect during our removal efforts, another cause of concern could be the recreational lobster fishery. With over 5,000 permits issued annually, and no training required for the permit holder, the potential for incorrect fishing methods for gear is high. Many of the derelict traps we recover in Cape Cod Bay are small and lightweight, which suggests they are recreational gear, rather than the heavier and larger commercial traps.

Our removal project allows us to bring these issues to the attention of state fisheries managers and provide them with information to assess existing regulations and consider changes that could reduce DFG in Cape Cod Bay. If you are a recreational lobsterman in Massachusetts, check out these instructional videos (a series of six) to learn the best practices for keeping your gear safe and secure in the water.