Guest blog by: Beth Polidoro, Associate Professor, Arizona State University

Located about 2,500 miles to the southwest of Hawai‘i, the U.S. unincorporated territory of American Samoa lies only a hundred miles and a jump across the international dateline from its cultural neighbor, the nation of Samoa. However, both islands share a fate similar to many Pacific island nations. Over the past few decades, problems with solid waste management have been exacerbated by limited space and a steadily increasing amount of imported goods and materials. The increase of lightweight, but not durable, plastic items are visible across much of the region’s coastlines, where plastic debris, such as food and beverage containers, household goods, and synthetic clothing, litter the shores.

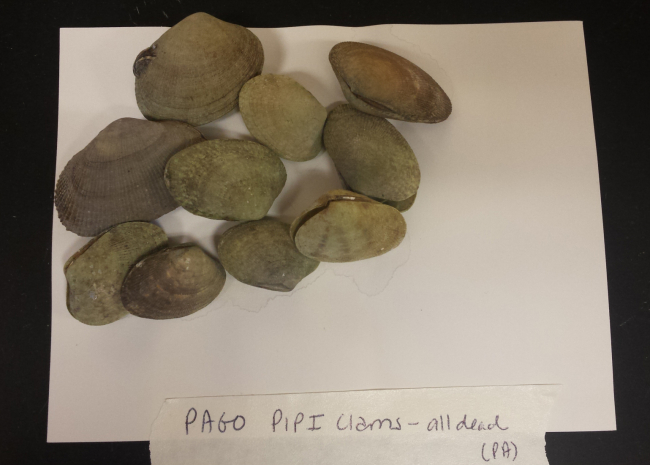

In collaboration with the American Samoa Environmental Protection Agency (ASEPA), the Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources (DMWR), and the American Samoa Community College (ASCC), Arizona State University (ASU) received a grant from the NOAA Marine Debris Program to quantify the amount of microplastics and associated contaminants in American Samoa’s marine waters and marine organisms. Between 2017 and 2019, students and faculty from ASCC and ASU, with logistical support from ASEPA and DMWR, collected marine waters, sediments, mussels, snails, and fishes from three locations on the main island of Tutuila. Once back at the ASU lab, samples were analyzed for microplastics, as well as pesticides and other organic contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Interestingly, both microplastics and contaminants were found to be highest in bivalves and snails, compared to marine waters, sediment, and fishes. The most commonly detected items, included microfibers from synthetic fabrics, PCBs, and a variety of persistent pesticides. However, based on measured amounts of contaminants and estimated human consumption rates, there is likely little potential health risk to local residents from eating locally caught mollusks and fishes. It is important to note, that as consumption rates or contaminant concentrations increase, risk levels can increase for segments of the population, such as children. In addition to human health risks, the potential ecological risks to the nearshore marine environment and marine life from plastics particles and organic contaminants are still difficult to estimate.

Regardless, mismanagement of solid waste can impact more than ecological and human health. The buildup of debris along beaches and in lagoons, and nearshore marine areas can also negatively impact livelihoods, tourism, and recreation by reducing opportunities for safe swimming and navigation, littering beaches, and diminishing fisheries harvests. We must all work together to find sustainable solutions to solid waste disposal. Beach cleanups will continue to stress resources and time if the never-ending stream of plastic and other waste cannot be stopped. Recycling, reusing, and repurposing are options, but can be expensive and market dependent. It may be time to rethink and redefine our relationship with plastic. Using data from research like this and working as a community, we can decrease the impacts of plastics in American Samoa and protect important marine habitat and food sources.

Is there a report from the U. of Arizona study? Could you please provide a link to the full report or published paper?