This blog was updated on April 11, 2023 to correct the species of trout selected for this study.

Guest blog by: Dr. Rob Hale, Professor, Department of Aquatic Health Sciences, Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS)

In the environment, animals may be exposed to many stressors at the same time, such as pollution, overfishing, and disease. Research suggests that animals exposed to microplastics and microfibers, or plastic pieces smaller than 5mm in size, may experience negative impacts to their immune system. In situations where an animal consumes microplastics, their immune system may be compromised and be less capable of dealing with additional stress, such as viral infections.

In order to better understand these relationships, our team, a collaboration between marine microbiologists, pathologists, immunologists, and environmental chemists at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), is investigating whether microplastics play a role in the onset and progression of infectious disease in fish with support from a NOAA Marine Debris Program Research grant. Because microplastics and their interactions with the environment are complex, our project focuses on specific types of plastic, microplastic sizes, and the relationship between a disease and the host, in this case rainbow trout.

Starting with the disease and host relationship, we selected rainbow trout because they are both environmentally and commercially important. The impacts of infectious diseases are a health problem for salmonid fishes worldwide and team microbiologist, Dr. Andrew Wargo, has already been studying this host-disease interaction in the lab at VIMS.

Our project is also unique due to our choices of microparticles, which include small fragments of a natural plant called Spartina. Spartina sp. is a widely distributed coastal marsh grass which naturally sheds tiny grass particles. Fish in the wild are exposed to microscopic plant particles, perhaps more so than to microplastics. This study is among the first microplastic studies to incorporate and evaluate the role of natural particles alongside synthetic plastics. The plastics identified for use in this study came from a number of field samples collected from aquaculture areas in Alaska.

The team at VIMS decided to use microplastics less than 20 microns in size (that is smaller than the width of a human hair). One reason the team decided to focus on this size of microplastics is that they are now being discovered as the most abundant microplastics in the environment. The team is also interested in this size because these very small particles are more likely to penetrate into fish tissues and cells, and affect fish health. The team decided to use polystyrene as a polymer type in their research because they expect that it will be a major component of the field-collected samples. Polystyrene is extremely common on the Alaskan coast due to its use in fishing floats and insulation, including coolers, and large amounts also washed up on the coast of Alaska after the 2011 tsunami in Japan.

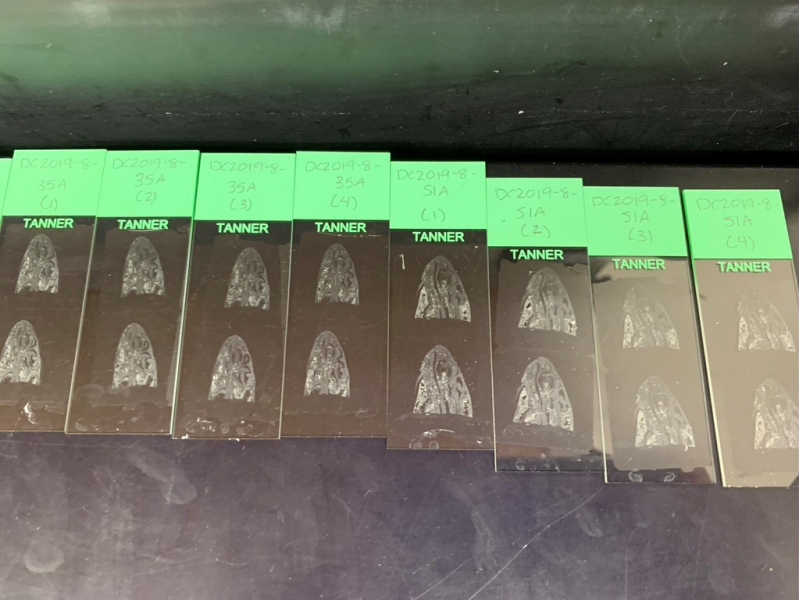

To date, the team has successfully generated microplastics from polystyrene and particles from Spartina for this experiment. Immunologist, Dr. Patty Zwollo, has begun working with immune cells and their response to polystyrene microplastics in the lab to examine possible impacts. A trial trout microplastics exposure was also performed to begin developing methods to track the travel of microplastics through the tissues of fish. The project’s next steps include evaluating the behavior of the Spartina microparticles in the fish and their response, as well as completing an analysis of the Alaskan field samples for microplastics. Stay tuned!

Such important research! I have been observing small styrofoam beads washing up in coastal Nova Scotia for several years, not really understanding what I was seeing or that it was harmful to fish, seabirds, shorebirds and other wildlife. Coastal water is now full of styrofoam from fishing buoys and especially from aquaculture, which floats on styrofoam. Styrofoam buoys and pontoons must be cheap because no one bothers to retrieve them following storms. Plastic coatings wear off and they break apart. Pieces of styrofoam are ubiquitous in the ocean and along the coast.