Guest blog by: Timothy Hoellein, Associate Professor, Loyola University Chicago, and Amy V. Uhrin, Chief Scientist, NOAA Marine Debris Program

Microplastics, or plastic pieces smaller than 5 millimeters in size, are common in the coastal waters of our ocean and the Great Lakes. Many ocean bivalves (mollusks with two hinged shells like mussels, clams, oysters, scallops) eat microplastics. When the bivalves are then eaten by fish, microplastics can be released into the fish’s gut during digestion resulting in trophic transfer, or when contaminants are passed from one level of the food chain up to another. Similarly, if freshwater bivalves eat plastic, they may also serve as a source for microplastics in freshwater food chains.

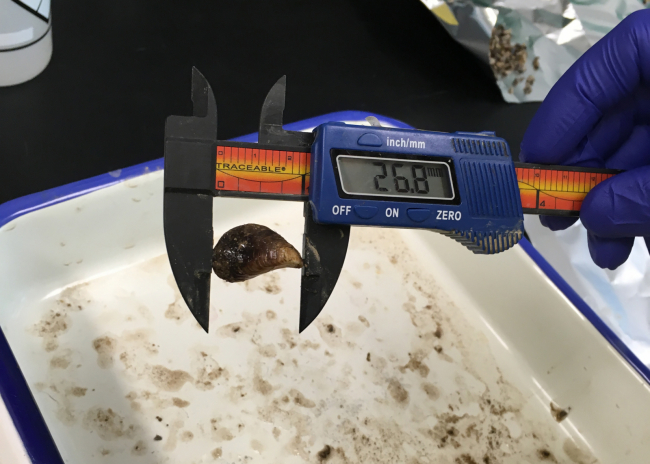

Since 1992, the NOAA Great Lakes Mussel Watch Program (GLMWP) has collected invasive zebra and quagga mussels from sites in the Great Lakes as part of its national contaminant monitoring program. Zebra and quagga mussels store contaminants in their bodies, a quality that suggests they may be useful as water quality biomonitors. Because they are stationary filter feeders, are abundant, and are relatively resistant to chemicals, their body tissues can be tested to reveal pollution where they live. Although zebra and quagga mussels are known to eat microplastics in a laboratory setting, scientists at both the NOAA GLMWP and the NOAA Marine Debris Program (MDP) were wondering, in the wild, do these invasive mussels take in microplastics along with chemical pollutants, and might they be indicators of microplastic pollution in the Great Lakes? In 2018, a team of marine scientists from NOAA MDP, NOAA GLMWP, and Loyola University Chicago joined forces to study this very question.

Mussels were collected from sites in the Milwaukee Estuary that were already part of the NOAA GLMWP, including nearshore sites and some farther into Lake Michigan. In addition, mussels were collected from two sites likely to have higher levels of microplastics: near a wastewater treatment plant outfall, and at the intersection of two urban rivers in downtown Milwaukee. We expected that mussels collected from sites with higher levels of microplastic would have higher amounts of microplastic in their tissue, as well as higher levels of chemical pollution.

We found microplastics in all mussel sizes and across all sites, and at similar concentrations to those reported from bivalves in other places around the world. However, our results showed that the concentrations of microplastics and chemical pollutants were highly variable across individual mussels and across study sites. Our study did not find evidence that mussels could serve as indicators of microplastic pollution, or that microplastics and chemical pollutants were associated with one another in mussel tissue.

We also noted the amount of microplastics in mussels was similar to fish from the Milwaukee River that were near the bottom of the food web, while microplastic levels were much higher in larger, predatory fish. Because microplastics were found in almost all zebra and quagga mussels, and they are so abundant, mussels are likely to influence the movement of plastic pollution through freshwater ecosystems, including potential impacts on the location of microplastics, and transfer through food webs. There is still much to learn about these possibilities.

Even though our predictions weren’t supported by the data, the conclusions we generated are founded on a fundamental process of scientific investigation, representing important steps in better understanding how our environment works. We are grateful for the opportunity to participate in this project, as it combined two important research programs at NOAA (bivalve monitoring and plastic pollution), contributed to understanding water pollution in freshwater ecosystems, and allowed for the participation and training of a large number of students. We hope that by staying curious about how our ecosystems work, and being open to new collaborations, we can all be best positioned to create positive impacts in our communities.

Learn more about this project by listening to the NOAA Ocean Podcast series “The Microplastic-Mussel Connection: Part One”, and “The Microplastic-Mussel Connection: Part Two.”