Join the NOAA Marine Debris Program as we celebrate National Ocean Month. This week’s theme is Ocean Science and our Chief Scientist recently discovered what it means to “catch marine debris” in the Hawaii-based pelagic longline fishery grounds.

We are pleased to share a recent paper that was published in the journal, Scientific Reports, by NOAA Marine Debris Program’s very own Chief Scientist, Amy V. Uhrin, in collaboration with the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, and Walsh Analytical Service. The paper discusses derelict fishing gear in the Hawaii-based pelagic longline fishery grounds, using NOAA fishery observer data. This work is believed to be the first comprehensive analysis of marine debris data gathered as part of a commercial fisheries observation program, a rare, novel, and opportunistic dataset.

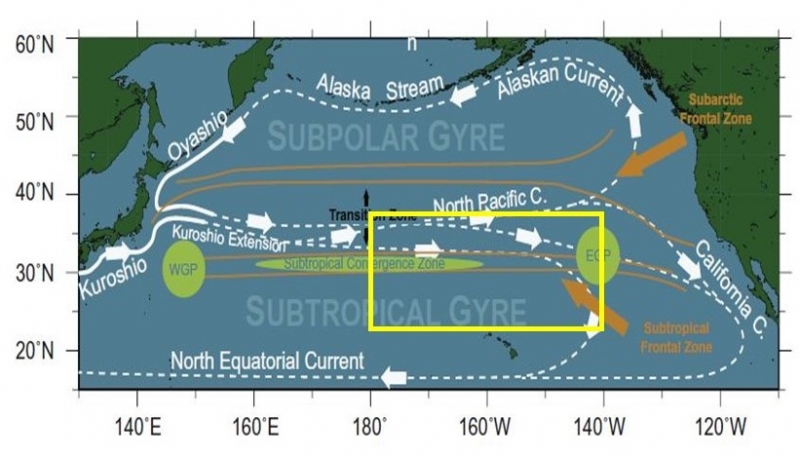

The Hawaii longline fleet operates in a region of the North Pacific Ocean that partially overlaps with the eastern part of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This area of the Pacific is of great research interest and public attention because rotating ocean currents called “gyres” collect large amounts of marine debris.

This study provides a unique look at the trends of marine debris in a remote and difficult to study area of the ocean. The paper has two key findings. First, although all marine debris types were considered in the analysis, nearly 90% of the items snagged by the longlines were derelict fishing gear from other fisheries operating in the North Pacific Ocean. Second, the study shows that the amount of derelict fishing gear snagged by the longlines has declined by two thirds (~66%) in less than a decade (2008-2016).

First, a little background about the data that informed the study. Fishery observers go out to sea aboard commercial fishing vessels to collect data from dozens of federally-managed fisheries for the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. These fishery observers are our eyes and ears on the water. They are trained biological scientists that gather first-hand data on what's caught and thrown back. The data they collect are used to monitor fisheries, assess fish populations, set fishing quotas, and inform management decisions.

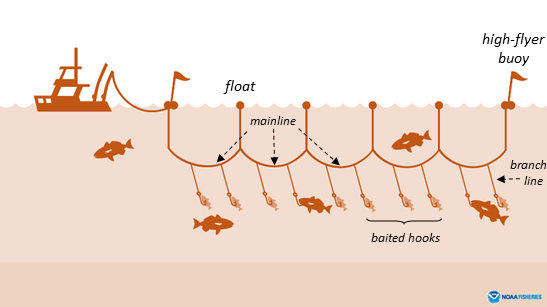

Fisheries observer data has been gathered since 1994 on the Hawaii-based pelagic longline fishery. In 2007, observers began recording data on the number and types of marine debris items snagged or “caught” by longlines. The marine debris data includes the type of item, and includes categories such as derelict fishing nets and lines/ropes, metal, and tarps.

The primary target species of the Hawaii longline fishery are bigeye tuna (in deep water) and swordfish (in shallow water). The longline vessels fish in a region of the North Pacific Ocean called the Subtropical Convergence Zone because this region supports high numbers of the smaller fish that bigeye tuna and swordfish like to eat. The Subtropical Convergence Zone is also an area where marine debris accumulates, as noted earlier. Here, it is not unusual for longlines to snag marine debris.

Dr. Uhrin wondered whether the marine debris data recorded by the fishery observers could serve as a way to estimate the relative abundance of marine debris in the Hawaii longline fishing grounds. Recent estimates suggest that derelict fishing nets comprise 46% of debris by mass reported within the boundaries of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Entanglement by derelict fishing gear is recognized as one of the greatest threats to seabirds, sea turtles, and marine mammals worldwide and threatens the ecology of the region, especially the Hawaiian archipelago.

The study shows a substantial decline in derelict fishing gear caught in the longlines and makes you ask, what is driving this apparent decline? It is possible that debris stranding in nearshore waters and on shorelines accompanied by decades of organized removal efforts in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands may have eliminated some derelict fishing gear from circulation, subsequently reducing the amount available for snagging by longlines. In addition, following the 2011 Tōhoku Japan earthquake and tsunami, over 30,000 fishing boats were lost in Japan. As a result, the total number of active Japanese commercial longline and purse seine vessels targeting the Pacific Ocean has declined substantially. Fewer active fishing vessels means fewer opportunities for lost gear, which may explain to a degree the observed decline. Nonetheless, with these data, the study authors could not definitively identify the causes of the decline over time.

The marine debris observations collected by the fishery observers in the Hawaii-based pelagic longline fishery, provide an opportunistic, but regular way to assess derelict fishing gear in a remote and difficult to study area. As we look to the future, although it may not be possible to rid the sea entirely of derelict fishing gear, many longline fishermen already voluntarily haul and stow snagged debris for disposal in port, effectively removing it from circulation. Future efforts to decrease this gear may include incentivizing at-sea removal by commercial fishermen to continue this at-sea behavior.

This study was a collaboration between the NOAA Marine Debris Program, the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, and Walsh Analytical Service. This study would not have been possible without the hard work of the Hawaii longline fishery observers and the agreement between the NOAA Marine Debris Program and the Pacific Islands Region Observer Program to collect these important data.