Guest blog by Dr. Jonathan Cohen, Associate Professor of Marine Science, University of Delaware and Dr. Tobias Kukulka, Associate Professor of Marine Science, University of Delaware

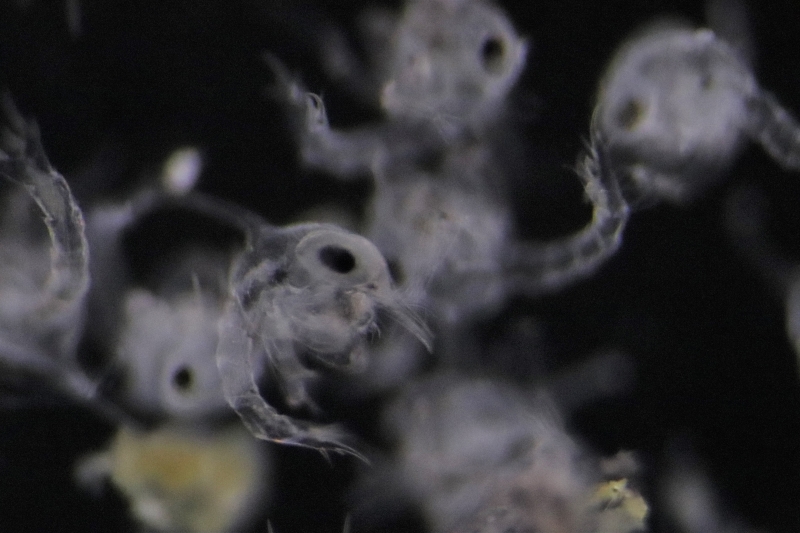

As warmer weather returns to the Atlantic coast, female blue crabs are waking up from a winter buried in the mud. They are making their way towards the open ocean where they release their offspring. These newly hatched spiny creatures, called “zoea larvae”, are smaller than a grain of rice. They’ll spend several weeks on a turbulent and windy voyage in the open, coastal ocean before returning to estuaries and coastal bays. Upon their return, they will eventually turn into adult crabs, and perhaps a crab cake once harvested.

Microplastics, or plastic pieces smaller than 5mm in size, are commonly found in our ocean and coastal waters. Do the microplastics that these larval crabs encounter while drifting in the ocean affect their survival and ability to return to estuaries? With support from a NOAA Marine Debris Program Research grant, a team of University of Delaware (UDEL) marine scientists have joined forces to study this question.

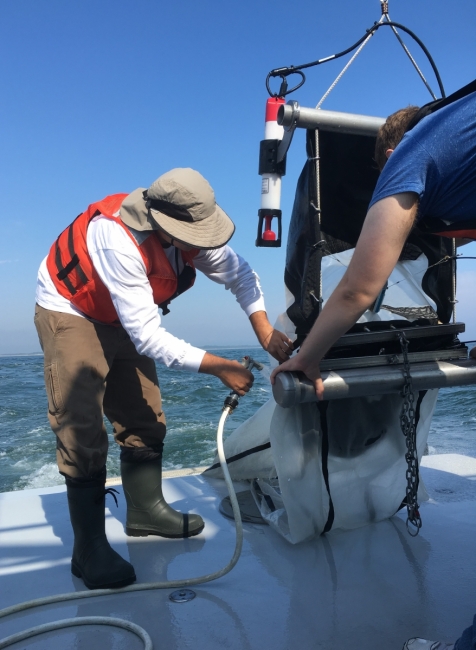

In just a few months, the team will be onboard the UDEL’s coastal research vessel, (R/V) Joanne Daiber, conducting surveys for both larvae and microplastics in the Atlantic Ocean offshore of the Delaware Bay. These surveys will provide the data that physical oceanographer Dr. Tobias Kukulka, and graduate student Todd Thoman, need in order to test computer models they are creating, which predict how microplastics and crab larvae circulate in the coastal ocean. These models will tell the researchers how much microplastic exposure crab larvae may have on their ocean journey. At the same time, biological oceanographer Dr. Jonathan Cohen, and graduate student Hayden Boettcher, will be raising blue crabs in the laboratory. In these experiments, the team can control the amount of microplastics the blue crab larvae are exposed to, and if their survival, growth and energy consumption are affected. Together, the computer models and lab data will allow the team to predict how and if larval blue crabs are impacted by microplastics. From there, researchers can begin to understand whether microplastics have the potential to impact the blue crab fishery.

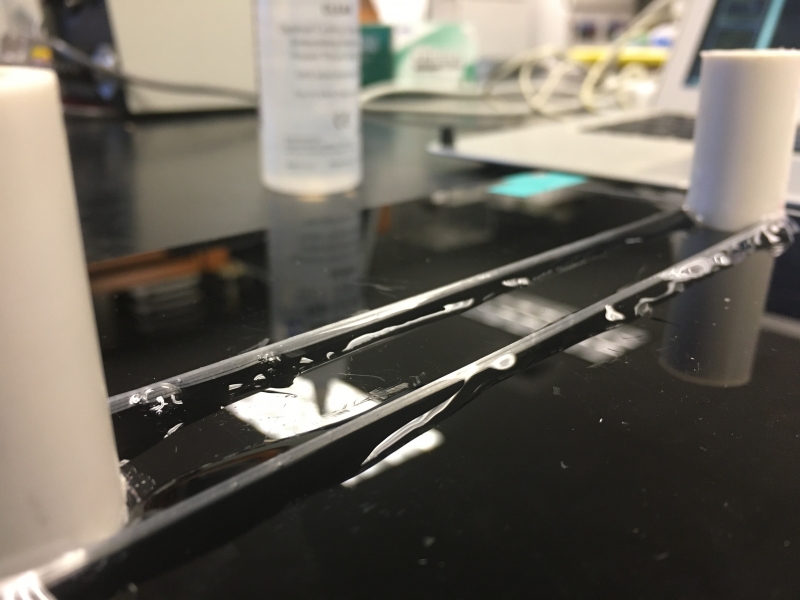

So what are researchers doing now to prepare for a busy field season? They are busy working on the computer models which will guide sampling activities and are replacing nets on the system used for collecting plastic and crab larvae. They are also calibrating the equipment used to measure the physics and chemistry of the water while sampling. Lastly, they are getting the lab ready to become home to thousands and thousands of crab larvae, which involves preparing the containers that will become homes for the larvae and microplastics to be used in the exposure experiments. It promises to be an exciting spring and summer as these scientists untangle the interactions of microplastics and blue crabs on the Atlantic coast!

¡Hola! me encantan los cangrejos y me gustaría saber ¿cuándo y dónde estarán disponibles los resultados de esta investigación?