Guest blog by Jennifer Repp, Graduate Researcher, University of Delaware College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment

What’s that noise? A quiet pinging in the distance? It’s getting closer. Okay, definitely a ping. It’s so fast, yet steady. It bounces off your side, echoing like a wave. What could it be? So quiet, so constant … and then, gone.

For you, a derelict crab pot from Delaware’s Indian River Bay, this will turn out to be a very unusual day. Up to 20,000 pots from Delaware’s recreational blue crab fishery may sit on the murky bottom of Delaware’s Inland Bays, getting swept around by the currents and mired in the mud. There, they await rescue – inadvertently scraping across the bottom, getting in the way of boats, and continuing to ghost fish by trapping crabs, fish, and other wildlife. Unfortunately, their buoys have been ripped free, and they sit unmarked, so no fisher will harvest the valuable blue crabs or release the vulnerable diamondback terrapins possibly ensnared within each pot.

It’s January 2021, in the midst of the off-season for the blue crab fishery, when you hear this gently pinging boat approach. It passes by once, twice, a strong hook grabs you and hoists you out of the mud, up into the sunlight.

And what of your rescuers? They are dedicated volunteers who come together in 30-degree weather with the mission of finding and removing as many derelict crab pots as possible. The project, led by the University of Delaware and Delaware Sea Grant, with the support of a NOAA Marine Debris removal grant, is identifying and recovering derelict crab pots lost and abandoned in Delaware’s Indian River Bay. This year, in only a day and a half, volunteers were able to remove 75 pots. Next year, with more sonar devices and round up events, their goal is to remove an additional 500.

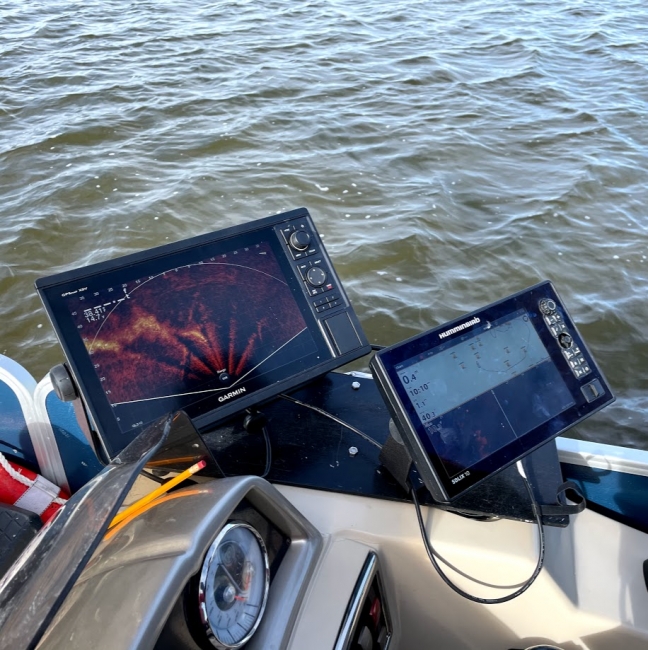

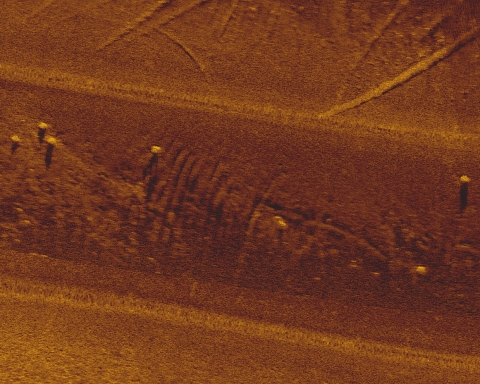

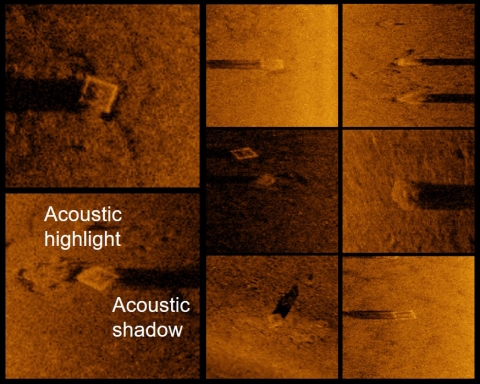

Now, back to that pinging. The noise you heard was from side-scan sonar, the technology that made your rescue possible. Low-cost and high-quality, the Humminbird Solix sonar system sends out sound waves, or pings, towards the bay floor. It listens to their echoes and creates images of the bottom and the objects on it, including crab pots. Researchers stitch this imagery together into an acoustic map of the bay floor and mark all the crab pots with points. During a recovery mission, volunteers motor to the points and use live sonar systems that serve as an underwater acoustic live-stream video to accurately aim their grappling hooks at the pots, otherwise invisible from the surface.

In addition to side-scan and live sonar, researchers at the University of Delaware are working to apply other advanced technologies to improve their efficiency at recovering derelict crab pots. They are deploying side-scan sonar on an autonomous surface vessel to survey the Inland Bays more efficiently than manned vessels alone. They are also developing machine-learning object detection methods to identify crab pots in the sonar imagery faster than humans can.

After recovery, some derelict crab pots will be refurbished and have another chance at fishing, others will become part of the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary’s living shoreline experiments, and the remainder will be recycled, all resting easy knowing that they are no longer ghost fishing and harming the Inland Bays’ environment.