Guest blog by: Kayla Mladinich, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut

Plastic particles less than 5mm in size, known as microplastics, are found everywhere that scientists have looked, including in the coastal waters of New England. The eastern oyster is an important commercial aquaculture species that has been shown to eat microplastics. Oysters are filter feeders, meaning they draw in and eat particles (small pieces of food and other materials) from the surrounding environment, including microplastics. However, oysters can select what is eaten or rejected depending on factors such as particle size and surface properties. This makes it unlikely that the types of microplastics ingested by oysters represent all the different types of microplastics in the environment.

Despite this, many scientists have suggested that oysters should be used to monitor and understand microplastic pollution in coastal waters. In partnership with the NOAA Marine Debris Program, marine scientists at the University of Connecticut sampled oysters in the field and performed a series of selection experiments in the laboratory to determine what types of microplastics oysters prefer to eat or reject and how that relates to what is in the natural environment.

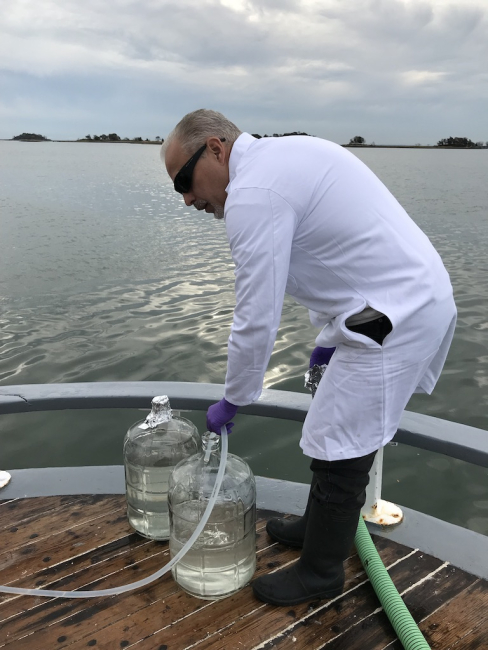

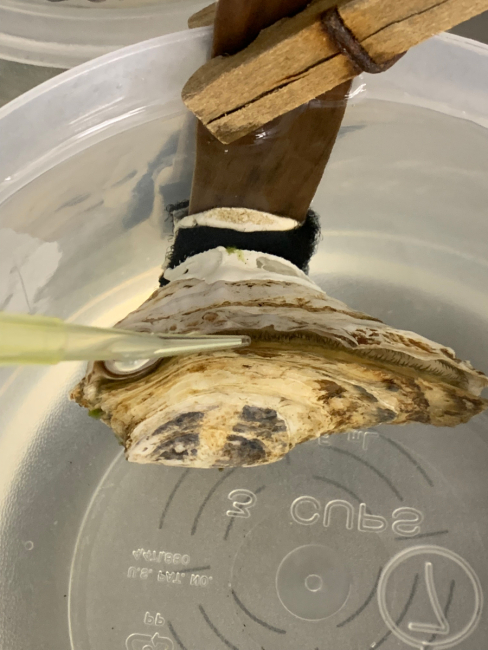

Oysters, sediment, water, and marine aggregates were sampled from a recreational oyster bed off the coast of Norwalk, Connecticut. For those of you who do not know what marine aggregates are, these are masses that form when particles, such as phytoplankton and fecal pellets, stick together in the water column before sinking to the bottom. Microplastics can be included into these masses at the surface and then eaten by oysters at the bottom. The shape, size, and plastic type of the microplastics were determined and compared across all sample types. In the laboratory, oysters were fed various combinations of microscopic fibers and beads of different sizes and types of plastic to explore what microplastics oysters chose to eat or reject.

The microplastics found in oysters did not align well with samples taken from their surrounding natural environment. No more than 16 microplastics were found in any individual sample, showing that microplastic concentrations in this area were low. The laboratory results indicate that oysters reject more larger particles than smaller ones and that the type of plastic does not influence selection. Laboratory results also demonstrate that most microplastics only stay in oysters for a few hours to a couple of days before leaving in feces. Taken together, data from this study suggest that the eastern oyster cannot be used to monitor microplastic pollution in nearshore waters but will still make a delicious appetizer at your favorite seaside restaurant.