Join the NOAA Marine Debris Program as we celebrate Clean Beaches Week, an annual event held July 1-7 each year.

Imagine that you are watching a small paper boat float on a lake and suddenly a breeze pushes the boat all the way across to the other side. You can no longer see it and the boat is too far away to pick up and you consider it lost. Now imagine that the paper boat is a large commercial fishing net, and instead of a lake, it’s traveling on currents in the ocean. It too has moved away from its original location, moved out into the open ocean, and is considered lost or derelict. Marine debris of all sizes can move around the ocean, being pushed around by wind and currents, and traveling to far off locations, such as the Hawaiian Islands.

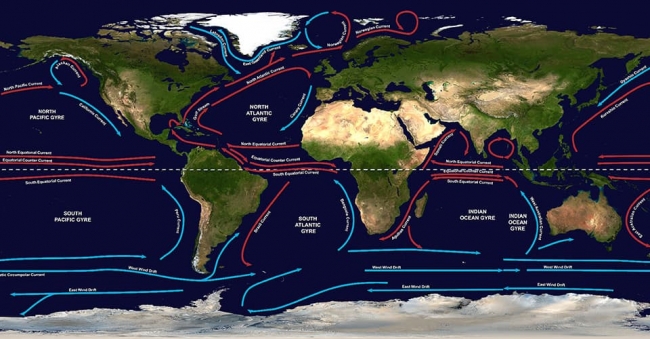

Wind, tides, and differences in temperature and salinity drive ocean currents. The ocean creates different types of currents, such as eddies, whirlpools, or deep ocean currents. Taken together, these larger and more permanent currents make up the systems of currents known as gyres. There are five major gyres: the North and South Pacific Subtropical Gyres, the North and South Atlantic Subtropical Gyres, and the Indian Ocean Subtropical Gyre. You can think of them as big whirlpools that pull objects into their center, forming areas where debris items can gather. Once the debris has been collected, it can be spread out at the surface of the ocean, float just below the surface, or sink all the way down to the seafloor making it difficult to locate and remove the debris.

The North Pacific Gyre contains the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the Hawaiian Islands, which is the most remote island chain in the world, yet beaches there are littered with marine debris. This chain of islands, or archipelago, also includes the Papahānaumokuāea Marine National Monument, a World Heritage Site, located northwest of the main islands. The ocean gyre in the region carries lost and abandoned fishing nets and gear from all over the Pacific Ocean, and because of where Hawaii is located within the gyre, this gear and other marine debris can build up in large amounts. The small islands and atolls act like a filter or comb in the center of the gyre, catching marine debris from the currents, and tangling nets on shallow coral reefs. The northeastern facing shorelines have the largest amount of marine debris build up, due to the consistent and strong trade winds.

Marine debris is difficult to address in Hawaii. The dense population, relatively small land mass, and geographic isolation present infrastructure and cost challenges. The NOAA Marine Debris Program (MDP) supports partner agencies, non-governmental organizations, and coastal communities in Hawaii that are working to prevent, reduce, and remove marine debris through a variety of projects.

The Papahānaumokuāea Marine National Monument marine debris removal mission efforts focus on surveying and cleaning up derelict fishing gear. In addition to fishing nets, buoys, and floats, there are also plastics, including bottles, bottle caps, cigarette lighters, toys, and toothbrushes that are collected and removed from the shore. Since 1996, these efforts have resulted in the removal of 923 metric tons (more than 2 million pounds) of primarily derelict fishing gear and plastics from the shorelines of the monument. That’s equivalent to about ten adult blue whales, which is the largest animal on the planet!

In 2018 the Hawaii Wildlife Fund, in partnership with Surfrider Foundation’s Kaua‘i Chapter and Pūlama Lānaʻi, with support from a Removal grant from the NOAA Marine Debris Program, continued to remove derelict fishing gear and medium- to large-scale marine debris items along impacted coastlines of the islands of Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i, Maui, and Lānaʻi. These islands receive a high volume of marine debris along its shores that impact wildlife. Hawaiian monk seals, hawksbill sea turtles, humpback whales, false killer whales, threatened green sea turtles, Pacific bottlenose, and spinner dolphins have all been negatively impacted by marine debris in Hawaii.

Two techniques are used to remove debris for this partnership: derelict fishing net/ large debris recovery workdays, also known as “net patrol”, and quarterly, community-based coastal cleanup events geared towards education, outreach, and local prevention efforts. At the end of the three year project, partners anticipate the total removal of at least 112 metric tons of marine debris from over 250 miles of coastlines across the four islands, and 1.5 years into this project they have already exceeded these numbers!

The Pacific Ocean bonds and connects many islands and people. Today, these island communities share in the struggle of reducing marine debris, as they work to protect the ocean. You can help protect the Pacific Ocean and its communities, including Hawaii, by learning more about the NOAA Marine Debris Program’s Pacific Islands Region and subscribe to the Hawaii Marine Debris Action Plan newsletter. Although these islands are 4,226 miles from the mainland United States, we can all work to prevent our trash from being carried on currents to this beautiful island chain.